Civil War Artillery: Basics

One of the things that is often over-looked (or mistreated, in my opinion) by most visitors to a battlefield is the artillery pieces that are on display. In most cases, these are actual weapons used during that period and fired in anger at the opposing force. They exist today because of careful preservation efforts and we’d like to keep them around for generations to come. This means that you probably shouldn’t let your kids treat them like playground equipment, OK?

Well, I’m not here to lecture you – at least not about your parenting. I’m here to talk about the guns themselves. Mini-rant over.

Gettysburg National Military Park has one of the best collections of Civil War-era artillery anywhere. While there are some fakes among the guns on the field (which have their own interesting history), most of the collection consists of the real thing. In this post, I’d like to focus on laying out some of the basics of Civil War artillery so that you too can become as much of a nerd for this stuff as I am!

First, let’s examine some of the different kinds of guns that were used during the Civil War.

As you may know, the Civil War marked several turning points in warfare. It was certainly a transitional period for tactics, but also for the technology employed in weapons and their manufacture. Some of these advances didn’t catch on right away, but you can see the beginnings of modern artillery in some of the pieces from this era.

The most visually-obvious advance was the use of metals other than bronze in the casting of cannons. Bronze was still in heavy use in the construction of weapons like the Model 1857 12-pounder Light Field Gun (the “Napoleon”), and in the Howitzers of the day, but iron was beginning to make an impact in weapons like the Parrott Rifle (mostly cast iron, with a wrought iron reinforce), and the 3-inch Ordnance Rifle (made entirely from wrought iron). These weapons were very strong and lighter-weight than their bronze counterparts. They were cheaper to produce (especially the Parrott design), and also did a much better job with another big innovation: rifling.

So we’re able to develop a basic identification guideline already: if a weapon is green (or greenish) it is made of bronze. If it is black, it is made of iron. The iron guns are ALL rifled (UPDATE: Well, maybe not). Very few of the bronze ones are.

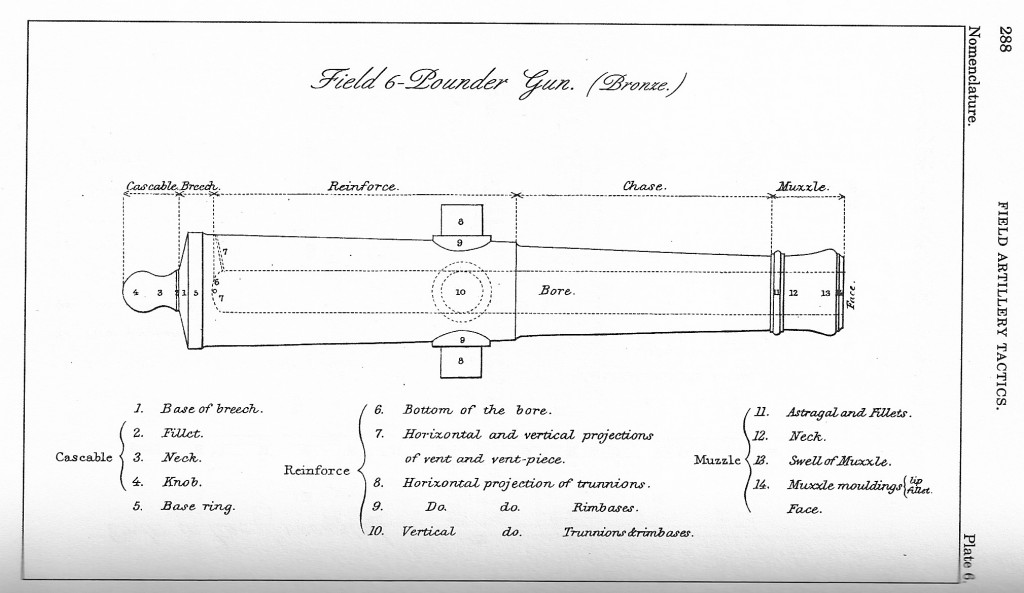

Now let’s have a look at some of the basic anatomy of these weapons:

While this diagram specifically refers to a 6-pounder gun (which was basically obsolete by the time of the Civil War), the same terms apply to all the other weapons of the period.

The important parts to note here are the breech, the muzzle, and the trunnions. These are the places where a cannon will bear marks that will help you to identify it. Information stamped onto a piece might include it’s manufacturer, serial number, weight, year of manufacture, and inspector’s initials. No visible markings on the piece is a pretty clear indication that it is a fake.

Let’s have a look at an example from Gettysburg:

On the left, the “No. 90” refers to this weapon being serial number 90. The serial numbers were unique to each manufacturer, so there may be as many as 6 or 7 U.S. number 90s. Sometimes the serial numbers were also done by orderer. This is especially true of the Parrott rifles. There was a “No. 1” that was made for the U.S. Army, AND a “No. 1” that was made for the Pennsylvania militia. It can get rather confusing.

Below the “No. 90” marking, are the initials “T.J.R” – this is the inspector’s mark (in this case, Thomas Jefferson Rodman) who ensured that the gun was fit for service. If it was, a “U.S.” mark was applied on the top of the barrel, near the trunnions. Moving counter-clockwise, we come to the “1862” mark, referring to the year this weapon was cast. The next marking, “1247 lbs.” obviously refers to the weight of the gun tube itself (not the full weight with the carriage and all).

On this example, the manufacturer’s mark is at the top of the muzzle:

It says “Revere Copper Co.” for those of you who have trouble reading it. Yes, it’s THAT Revere. While we all know him for his revolutionary exploits (including a certain late-night ride), that was not his entire life story, of course. His real business was silversmithing and in the post-revolutionary period he did so well for himself that he expanded his business into copper, brass, and iron works. While not the largest supplier of artillery, there are a few examples of his company’s work at Gettysburg, and to my eye, they are the ones with the highest level of craftsmanship. They seem to always have a very bright and consistent green color and just take a look at the “U.S.” stamp on top of the tube:

So we can tell a lot about this particular weapon by the markings. First, it is a REAL one. Since we know it was made by Revere Copper Co. in 1862 with a “U.S.” mark, we can also deduce that it was made in Boston, MA and purchased by the U.S. Army specifically for the war effort (since the war went on from 1861-1865). It was likely actually used in battle. The weight of the piece determined the price (usually between $0.40-$0.50 per pound), so that tells us that it probably cost the government between $500-$600 at the time (between $11,500-$13,000 in 2010 dollars) to buy. The fact that it is a bright, consistent green color tells us that it used a pretty high-quality bronze. Some of the Confederate guns in particular are a dingy grayish-green color; a result of metals like iron and lead being mixed into the bronze because the south couldn’t produce or smuggle-in enough copper. Confederate guns may also have bright green dots scattered on them. These are plugs that were put in after the gun was cast to fill in imperfections in the metal.

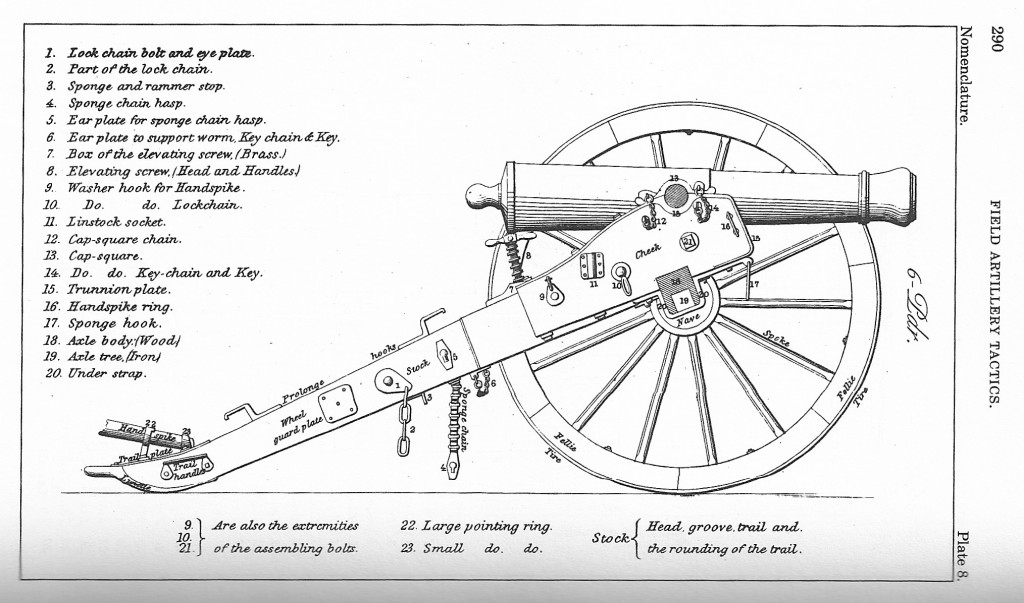

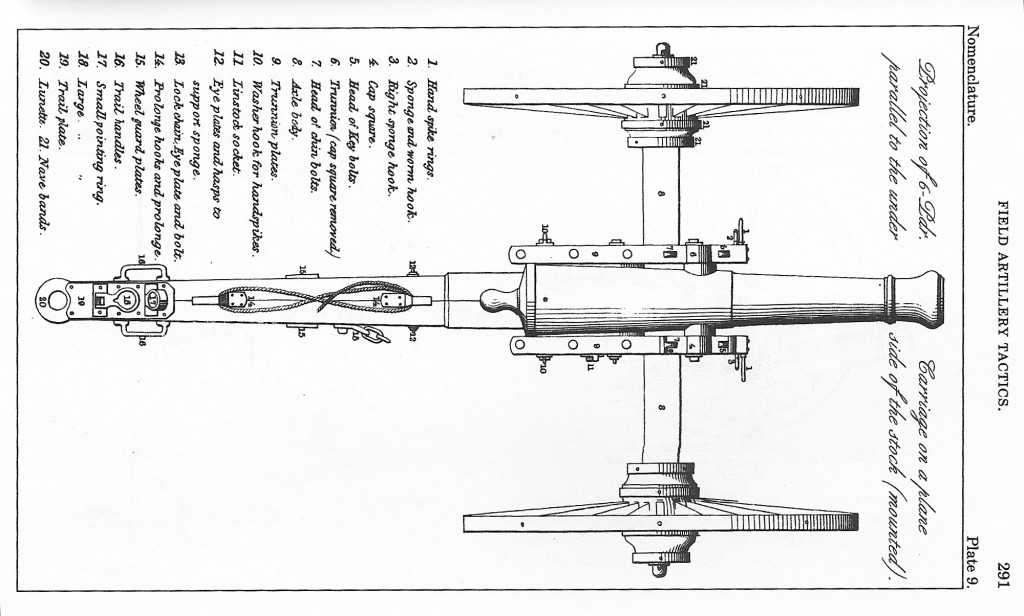

Another important part of the artillery is the carriages that the weapons are mounted to for field use. A gun without a carriage is pretty useless. During the Civil War, these were made from wood for ease of construction and to keep them lightweight. The problem with wood carriages in a static, “museum” atmosphere is that they don’t weather very well. The carriages at Gettysburg (and on every battlefield I’ve ever been to) are reproductions made out of steel and painted to appear as they would have. All the normal pieces are present on these copies, though:

Terms like “prolonge” and “elevating screw” tend to come up in official descriptions of battle action, so it’s handy to know what parts these are referring to.

Now that the basics are out of the way, I’m planning to do a series of posts on this topic. Among the other things I want to cover are the mechanics of how these pieces were fired; how they were arranged into sections, batteries, and battalions (including command structure); and a few posts on specific weapons in the Gettysburg collection that are unique or interesting.

Stay tuned!

OK, dumb question. I’ve seen the cannons at Gettysburg, Pea Ridge and Wilson’s Creek battlefields and they seemed to have the same blueish-green/gray color as seen in the photos above, which I take it means they were bronze pieces rather than iron. Basically the same color as the Statue of Liberty. Now my question is: is this blueish-green/gray color a result of weathering, being exposed to the elements for 150 years? Meaning they were originally a shiny and more golden bronze color? Or is this the color they were originally?

Novice,

The blueish-green/gray color is a patina. That’s what happens to copper as it “rusts”. So you are correct in your assumption that this was caused by the guns weathering for well over 100 years. Originally, they would have been a bright, metallic bronze color (depending on the quality of the metals used in manufacturing, of course – I’d assume that some of the later Confederate guns would have appeared to be more dull as they used more lead in the place of copper). There are a few fake Napoleans at Monocacy that try to exhibit the look they would have had at the time of the fighting. You can see my post about Monocacy here:

http://pete.skilmnet.net/2013/06/monocacy-visit/

I’m superintendent of oak Hill Cemetery in Taylorville IL. We have for Parrott Cannons. Is it possible to tell me anything about these cannons. Or put me in touch with someone. We have just had our cannons restore.

The marking are:

1862 20 pdr 3.67 p rpp no. 120 1795 lbs,

1865 20 pdr 3.67 p rpp no. 326 1725 lbs this one has R.B.H

1861 20 pdr 3.67 p rpp no. 98 1795 lbs

1861 20 pdr 3.67 p rpp no. 103 1828 lbs

Bill,

That’s a very interesting collection! What you have there is a collection of 20-pounder Parrott Rifles (so named because the solid-shot projectile they fired weighed 20 lbs). The gun was invented by Robert Parker Parrott, and manufactured at his West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, NY – across the Hudson from the United States Military Academy. There were Confederate copies of his design, but you have the genuine article there on all counts. This was one of the larger guns that would have been considered field artillery, and they were not used often because they were so much larger, heavier, and more unwieldy than the more common 10-pdr and 12-pdr field guns.

The “3.67” marking indicates the caliber – just another way to describe the ammunition it fired – a shot that was 3.67″ in diameter.

The records for almost all of the surviving examples of this model of gun are certainly incomplete – from when they were brought into service, to where they actually served, to where they ended up. The thought is that many were melted down in the years after the war. What’s really cool is that all of your guns there are listed as “unknowns” in the resources I have. I guess they aren’t anymore!

Here’s what I have:

Serial Number 98 – Seems to have been inspected by Robert Parker Parrott himself. While it was manufactured in 1861, it doesn’t look like this one was accepted by the U.S. Army until July 17, 1862. I have no record to indicate where this gun may have served.

Serial Number 103 – Seems to have been inspected by Robert Parker Parrott himself. While it was manufactured in 1861, it doesn’t look like this one was accepted by the U.S. Army until July 17, 1862. I have no record to indicate where this gun may have served. It’s also worth noting that this is the heaviest 20-pdr Parrott I’ve seen at 1828 lbs.

Serial Number 120 – This one was inspected by Alfred Mordecai (there should be an “A.M.” stamped somewhere on it – perhaps on the ends of the trunnions?). Though it was made in 1862, it was accepted on January 27, 1863. Again, no service records here.

Serial Number 326 – This is the most exciting one. Like I said before, the records for these weapons are incomplete. The highest serial number that I’m aware of records for was 296, so we knew that at least that many were produced. Your information would seem to indicate that there were at least 326 of the 20-pdrs made. Since this weapon was made at the end of the war in 1865, it may have just been made at the last minute to satisfy a contract, and was never really intended to see action. It’s hard to know. I know that number 296 was made in 1864, so this would be the only 1865 20-pdr I’ve come across. The “R.B.H.” marking is curious – is it possible that you’re mis-reading it, and that it is in fact, “R.M.H.”? That would indicate the inspector was Richard Mason Hill. He’s listed as the inspector for the last batch of guns I have records for (numbers 272-296).

Thank you very much. I did not know any of this informaion. I re-check No. 326, the letters are clearly R.B.H on the left hand side of the circle where the gun pivots up and down. How much are there cannons worth, I guess to a collector?

Thanks again

Bill

Hello, I am the “novice” that asked the question above about the coloration of the bronze field pieces. Thank you so much for answering my question. In the months since I’ve gotten really interested in Civil War artillery and now know a little more about it than I did at the time. I had no idea so many types of artillery pieces served in the war! I’m now trying to gather pictures of all of the artillery piece types, starting with the Union.

I was wondering though if maybe you might be able to help me with something. I can’t find anywhere a picture of two types of artillery pieces and I was hoping maybe you might have one. I can’t find anywhere a picture of a 3.67-in. Sawyer Rifle or one of the lesser-known makes of 6-pdr., the Model 1840. Now I have pictures of 6-pdrs. going back to the Model 1819 “Walking Stick” gun, the Model 1835, and I have of course the ubiquitous Model 1841 main production model. But I found out yesterday that there was also a Model 1840 which was produced in small numbers, about 30 or 40 at most, but I can’t find any pictures of it. Same with the Sawyer Rifle, I could only find a drawing of some gigantic Columbiad looking gun that was apparently also invented by Sylvanus Sawyer but not his 3.67-in. gun. Any help you could render would be greatly appreciated. And thanks for making such a great blog and for answering my original question. Best wishes to you and yours.